The Panel Stack Pattern

–Ь–∞—В–µ—А–Є–∞–ї –Є–Ј Wiki.crossplatform.ru

|

|

| Qt Quarterly | –Т—Л–њ—Г—Б–Ї 27 | –Ф–Њ–Ї—Г–Љ–µ–љ—В–∞—Ж–Є—П | |

by Johan Thelin

When reading about Qt for Embedded Linux, many examples seen in the online press are related to media gizmos, mobile phones and other graphics-intensive applications. One common, but less discussed application is in control panels, used for home automation, industrial machinery and alarm systems.

–°–Њ–і–µ—А–ґ–∞–љ–Є–µ |

The typical control panel does not feature a windowed interface. It does not run multiple user applications at once. They generally do not feature a full sized keyboard. Instead a touch screen or a very basic set of buttons is used.

In this article, I will present a basic pattern that I've been using when implementing this type of applications. I call it a pattern because each of these systems that I've come across has its own peculiarities and it is hard to make them all in one mould.

[–њ—А–∞–≤–Є—В—М] The Stack

All these systems are based around full screen dialogs—I choose to call these panels. Most of these panels are fairly static and can thus be created at start-up. To avoid having to create them all at once, the singleton pattern can be used. This postpones the creation of panels until they are first used, but prevents them from being created more than once.

We will wait just a few moments with this code as there is one important building block that forms the basis of the pattern: the panel stack. All panels are kept in a QStackedWidget. This stack of panels is kept in a widget that acts as the application's "main window". As there can be only one main window, this is a singleton class and it is called the PanelStack. The panel stack holds all the panels and lets you show each one of them in turn by referring to the index that you get when you add it to the stack.

class PanelStack : public QWidget { Q_OBJECT public: static PanelStack *instance(); int addPanel(AbstractPanel *); void showPanel(int); private: ... };

So, each panel is actually an implementation of AbstractPanel, and almost all panels are singletons. The idea is that, the first time an instance of a panel is called, it adds itself to the panel stack. Then, each panel provides a method called showPanel(). It initializes the panel and tells the panel stack to show it. This means that each panel keeps its own index, and all that you need to know when implementing your application is that you call showPanel() in the panel that you want to show.

class AbstractPanel : public QWidget { protected: AbstractPanel(QWidget *parent = 0); void addPanelToStack(); int panelIndex() const; private: ... };

The actual singleton implementation is made in each subclass of AbstractPanel. That is also where the showPanel() method is added. I have left out a virtual showPanel() method, as different panels need different arguments when being initialized.

[–њ—А–∞–≤–Є—В—М] An Example

Let's continue by looking at an example. In this case, a VCR control panel. It consists of four panels: the main menu, the live panel (holding the play, pause and stop buttons), the recordings panel (allowing the user to manage schedules for recording), and finally, the recording details panel (letting the user configure a given schedule for recording).

Each of these panels will be designed using Qt Designer and their interface will look very much the same. We will focus on the RecordingsPanel widget in this article. The entire example is available for download from the Qt Quarterly Web site.

Before we continue, a short word about keeping data away from the user interface code. We use a recordings class in parallel to the panel classes shown here and the panel stack class. This allows all panels to access the data independently of each other.

In this trivial example, we use a QStringList to keep all the recordings, but in a real world application this would most probably be a singleton, possibly coupled with a QAbstractModel interface. We start by declaring the class as a singleton and providing the showPanel() method. In this case, the panel always shows all recordings, so there is no need for arguments.

class RecordingsPanel : public AbstractPanel { public: static RecordingsPanel *instance(); void showPanel(); ... private: RecordingsPanel(); static RecordingsPanel *m_instance; ... };

The implementation follows. Notice that the implementation method adds the panel to the stack. This is to allow the addPanel() method to use methods, signals and slots of the actual class being implemented and not the base class. If the addPanelToStack() call had been made from the AbstractPanel's constructor, the virtual methods, signals and slots would have been those of the AbstractPanel and not of the RecordingsPanel.

RecordingsPanel *RecordingsPanel::m_instance = 0; RecordingsPanel *RecordingsPanel::instance() { if (!m_instance) { m_instance = new RecordingsPanel(); m_instance->addPanelToStack(); } return m_instance; } void RecordingsPanel::showPanel() { PanelStack::instance()->showPanel(panelIndex()); }

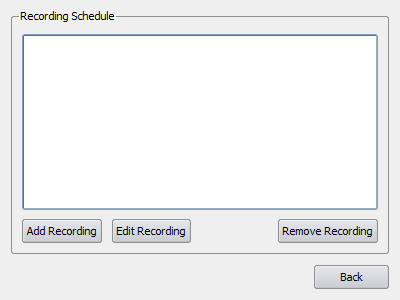

The singleton pattern, as shown above, is used for all panels. Now looking at the panel itself (in the image opposite) you can see that this panel consists of a list of recordings and four buttons. Each of these buttons has a corresponding slot.

class RecordingsPanel : public AbstractPanel { public: static RecordingsPanel *instance(); void showPanel(); private slots: void addClicked(); void editClicked(); void removeClicked(); void backClicked(); };

The slots leading to navigation between panels are add(), edit() and back(). The Remove Recording button simply removes a recording from the list, but keeps showing the list.

The Back button asks the main menu to show itself using the showPanel() method, while the Add Recording and Edit Recording buttons pass on the recording's index to the recording details panel. For new recordings, an index of -1 is passed to indicate that a new recording is to be created.

void RecordingsPanel::addClicked() { RecordingDetailsPanel::instance()->showPanel(-1); } void RecordingsPanel::editClicked() { RecordingDetailsPanel::instance()->showPanel( ui.recordingsList->currentRow()); } void RecordingsPanel::backClicked() { MainMenu::instance()->showPanel(); }

In the RecordingDetailsPanel class, the showPanel() method looks at then initializes the user interface accordingly.

void RecordingDetailsPanel::showPanel(int recordIndex) { m_currentIndex = recordIndex; if (m_currentIndex == -1) ui.lineEdit->setText(""); else ui.lineEdit->setText(recordings[m_currentIndex]); PanelStack::instance()->showPanel(panelIndex()); }

The implementation of the panel stack to handle this case is fairly trivial. The widget more or less wraps a QStackedWidget. When adding a panel to the PanelStack, it adds the panel to its QStackedWidget and returns the relevant index.

int PanelStack::addPanel(AbstractPanel *panel) { return m_panelStack->addWidget(panel); }

In a similiar fashion, the showPanel() method simply changes the currently shown widget in the stacked widget.

void PanelStack::showPanel(int index) { m_panelStack->setCurrentIndex(index); }

Just wrapping a widget in another widget is not a good way to move forward. However, if we add some functionality to the panel stack we can start to make some gains. We'll examine one way to do this in the next section.

[–њ—А–∞–≤–Є—В—М] Keeping History in the Stack

In the previous example, we built a set of panels that are navigated according to a static pattern. Clicking Back when in the recordings panel always leads to the main menu, and so on. This is all very well in most small systems, but it means that we cannot reuse panels in different places in the navigation tree.

To avoid this problem, we can keep the navigation history in the panel stack. Each time a panel is shown, its index is added to a history stack. Instead of moving to the parent when leaving, a back() method is added to the panel stack. This moves one step back in the history stack until the first panel is encountered. In the true spirit of the Web browser metaphor, a home() method is also added. It takes us all the way to the first panel in one simple call.

Panel reuse is one of the benefits of using this pattern. Another benefit is that the source code dependencies are reduced: each panel only needs to know of the panel stack and the panels located deeper in the navigation trees. The parent panels are no longer important. Finally, we make the back() and home() methods slots, thus removing the need for those slots in the panels.

class PanelStack : public QWidget { ... int addPanel(AbstractPanel *); void showPanel(int); public slots: void back(); void home(); private: ... };

The changes that we need to make involve creating the m_history stack and pushing indexes onto it when showPanel() is called. When back() is called, we pop one index off, and when home() is called we pop all but one index off it.

void PanelStack::showPanel(int index) { m_history.push(index); showTopPanel(); } void PanelStack::back() { if (m_history.count() <= 1) return; // Cannot go back past the first panel. m_history.pop(); showTopPanel(); } void PanelStack::home() { if (m_history.count() <= 1) // Either already home return; // or there are no panels to return to. while (m_history.count() > 1) m_history.pop(); showTopPanel(); }

This design forces a rule on the user—the first panel shown is the menu and you cannot pop the history beyond that. As you can see, the home(), back() and showPanel() methods do not update the widget stack themselves. Instead they call the showTopPanel() method. This is a private method that takes care of the details.

void PanelStack::showTopPanel() { m_panelStack->setCurrentIndex(m_history.top()); dynamic_cast<AbstractPanel*>(m_panelStack->widget( m_history.top()))->enterPanel(); }

It not only shows the right panel, but it calls the enterPanel() method of that panel. The enterPanel() method is a virtual method added to the AbstractPanel class. The default implementation is a dummy one that does nothing.

The idea here is that a panel can appear both as a result of its showPanel() method being called and from a panel stack event, resulting from a call to home() or back(). In the latter case the panel needs to know that it is about to be shown so that it can update its contents. For example, the recordings panel updates its list of recordings here.

[–њ—А–∞–≤–Є—В—М] Pulling Apart the Stack

We now have a method that we know is called every time a new panel is about to be shown. So, why not use it to update some common parts of the user interface. For instance, if a title bar is a part of every panel, why not place it in the panel stack and add a virtual method called titleText() to each abstract panel?

class AbstractPanel : public QWidget { public: virtual void enterPanel() {} virtual QString titleText() const = 0; ... };

A small change to the panel stack updates the m_titleLabel label each time a new panel is changed.

void PanelStack::showTopPanel() { m_panelStack->setCurrentIndex( m_history.top() ); AbstractPanel *panel = dynamic_cast<AbstractPanel*>( m_panelStack->widget(m_history.top())); panel->enterPanel(); m_titleLabel->setText(panel->titleText()); }

There are numerous other elements that can be added to the panel stack to form a common infrastructure. If nothing else, Back and Home buttons, and perhaps a couple of shortcut buttons leading to specific forms. The buttons can then be hidden and shown by adding virtual methods such as hasBack() and hasHome() to the AbstractPanel class.

[–њ—А–∞–≤–Є—В—М] More through the Stack

The stacked approach does not only allow for the transfer of information from the panels to the stack. It can work the other way around, too. This is very helpful when dealing with systems with rudimentary control methods.

For example, implementing a keyboard plugin for a keypad consisting of four buttons placed next to the screen can feel like an overkill solution. Instead, one can intercept the events in the panel stack and, from that stack, pass the events on to the current panel through a set of virtual methods. A custom solution, yes, but as you are probably dealing with custom hardware that is only to be expected.

I have found the panel stack approach useful in numerous customer cases and it always performs well while being flexible and adaptable to application-specific requirements. I hope you find it to be a useful way to think about embedded user interfaces.

The source code for the example described in this article can be obtained from the Qt Quarterly Web site.